Unit-2

Table of Contents

QUESTION-Explain the key terms defined under the Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887, such as ‘tenant’, ‘landlord’, ‘rent’, and ‘ejectment’, and their significance in the context of land tenancy relations

Key Terms Defined Under the Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887

The Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887, regulates the relations between landlords and tenants in Punjab. It defines several key terms that are vital to understanding the rights, responsibilities, and legal proceedings related to land tenancy. Below are the key terms along with their significance in the context of land tenancy relations, with reference to relevant sections of the Act:

1. Tenant (Section 4)

- Definition: A tenant is a person who holds land or a portion of land from a landlord under a lease, whether oral or written, and pays rent for the use of the land. A tenant may be a permanent tenant, occupancy tenant, or non-occupancy tenant depending on the nature of their tenure.

- Significance: The definition of tenant is crucial because it determines who is entitled to the legal protections provided by the Act. Tenants have rights regarding the occupation and enjoyment of the land they cultivate, and the law outlines these rights specifically to ensure that tenants are not unjustly ejected or exploited by landlords.

2. Landlord (Section 5)

- Definition: A landlord is the person who owns the land and has leased or let it out to a tenant. A landlord may also be a person entitled to receive rent or who has control over the land.

- Significance: The landlord-tenant relationship is fundamental to the Act, as it governs the terms of tenancy, including the payment of rent and the conditions under which a tenant can be evicted. Understanding who qualifies as a landlord ensures that landlords’ rights to collect rent and manage land are recognized and protected.

3. Rent (Section 9)

- Definition: Rent refers to the amount paid by the tenant to the landlord for the use of the land or property. The rent is typically agreed upon in advance and must be reasonable and fair. The Act provides for the regulation of rent payments and ensures that rents are not arbitrary.

- Significance: Rent is a key term because it establishes the financial relationship between the landlord and tenant. The Act provides provisions regarding the payment of rent, the permissible amount of rent, and the consequences of non-payment. For example, Section 9(2) prohibits the landlord from charging exorbitant rent, ensuring the protection of tenants from exploitation.

4. Ejectment (Section 39)

- Definition: Ejectment refers to the legal process through which a landlord seeks to remove a tenant from the land. A landlord may seek to eject a tenant for various reasons, including non-payment of rent, breach of tenancy conditions, or illegal use of the land.

- Significance: Ejectment is an essential part of land tenancy relations because it determines under what circumstances a landlord can remove a tenant. Section 39 specifies the conditions under which a tenant can be ejected. These include failure to pay rent, the tenant’s violation of lease terms, or the tenant’s inability to maintain the property. The law protects tenants from arbitrary ejectment, ensuring that a landlord cannot forcibly remove a tenant without following the proper legal procedure.

Legal Framework for Ejectment (Section 40 and 41)

- Section 40: The landlord can apply to the Revenue Officer for ejectment if the tenant has defaulted on rent for a specific period. However, the tenant has the right to contest this application.

- Section 41: The Revenue Officer is empowered to decide on the ejectment and can allow a tenant to remain on the land if the tenant can prove valid reasons for non-payment or other justifiable circumstances.

Conclusion

The definitions of key terms such as tenant, landlord, rent, and ejectment under the Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887 are crucial in understanding the legal framework that governs land tenancy relations. The Act aims to balance the rights and duties of both landlords and tenants, ensuring that tenants are protected from exploitation while allowing landlords to manage their land effectively. Each term has specific legal implications that guide the conduct of both parties in a tenancy relationship. The Act’s provisions regarding rent, tenancy conditions, and the process of ejectment ensure that land transactions remain fair and just, with legal safeguards for all involved.

Question-Discuss the different classes of tenants under the Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887. How do the rights and responsibilities of each class differ in terms of rent payment, occupancy, and ejectment?

Classes of Tenants Under the Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887

The Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887, classifies tenants based on the nature of their tenancy rights and the security of their tenure. These classifications determine the rights and responsibilities of tenants regarding rent payment, occupancy, and ejectment. The Act recognizes the following main classes of tenants:

1. Occupancy Tenants (Section 5)

Definition:

An occupancy tenant is a tenant who has the right to cultivate the land for an indefinite period, and whose tenancy is hereditary. This means that the tenant and their heirs have the right to occupy and cultivate the land, subject to the terms of the tenancy agreement.

Rights and Responsibilities:

- Rent Payment: Occupancy tenants are usually required to pay a fixed rent, which is agreed upon by the landlord and tenant. The rent may be less than that charged to non-occupancy tenants due to the permanence of the occupancy.

- Occupancy Rights: They have a right to remain on the land as long as they fulfill the tenancy conditions, particularly the payment of rent. Their right to occupy the land is hereditary, and the tenant’s heirs are entitled to continue cultivating the land.

- Ejectment: Occupancy tenants enjoy a strong legal protection from ejectment. They can only be ejected by the landlord on specific grounds, such as non-payment of rent or other breaches of the tenancy agreement. Section 40 allows the landlord to apply for ejectment under certain conditions, but occupancy tenants have a greater level of security than other tenants.

2. Non-Occupancy Tenants (Section 5)

Definition:

A non-occupancy tenant is a tenant who does not have the hereditary right to occupy the land. This class of tenants has limited security and can be evicted more easily than an occupancy tenant. The tenancy agreement for non-occupancy tenants is typically for a specified period or based on the landlord’s discretion.

Rights and Responsibilities:

- Rent Payment: Non-occupancy tenants are required to pay a specified rent, which is often higher than the rent paid by occupancy tenants. The rent is agreed upon at the start of the tenancy agreement, and the terms can vary based on the landlord’s discretion.

- Occupancy Rights: Non-occupancy tenants do not have permanent or hereditary rights to occupy the land. Their right to cultivate the land depends on the landlord’s consent and the terms of the tenancy agreement.

- Ejectment: Non-occupancy tenants can be evicted more easily than occupancy tenants. The landlord has more flexibility in terminating the lease or evicting the tenant, often with less formal procedures. However, the tenant still has some protection under the law if they have a legitimate reason to contest an ejectment.

3. Permanent Tenants (Section 6)

Definition:

A permanent tenant is a tenant who has been granted a lease on the land for an indefinite period, and the tenancy cannot be terminated by the landlord unless specific conditions are met. This class of tenants has the most secure tenure, but their rights are not hereditary, unlike occupancy tenants.

Rights and Responsibilities:

- Rent Payment: Permanent tenants generally pay a fixed rent that is agreed upon at the time of the lease. However, the rent paid by permanent tenants is typically higher than that of occupancy tenants, but lower than non-occupancy tenants in some cases.

- Occupancy Rights: The tenant’s right to occupy the land is secure and cannot be terminated by the landlord without sufficient cause. However, unlike occupancy tenants, their tenure is not automatically passed on to their heirs.

- Ejectment: Permanent tenants can be evicted only under specific legal grounds, such as non-payment of rent or other breaches of the lease agreement. Their tenancy is protected under the law, and they have a strong claim to remain on the land if they fulfill their obligations.

4. Tenant at Will (Section 6)

Definition:

A tenant at will is a tenant who occupies land with the landlord’s consent but without a formal lease agreement or fixed term. This type of tenancy is informal and can be terminated at any time by either the landlord or the tenant.

Rights and Responsibilities:

- Rent Payment: The rent for tenants at will may be decided on an ad-hoc basis, often depending on the mutual agreement between the tenant and landlord.

- Occupancy Rights: Tenants at will have very limited rights regarding occupancy. They do not have a formal lease, and their occupancy can be terminated at any time by the landlord, typically without cause or legal restrictions.

- Ejectment: Tenants at will are the most vulnerable to eviction and can be ejected by the landlord at any time without any formal legal process, provided the landlord gives reasonable notice.

5. Tenant for a Term Certain (Section 6)

Definition:

A tenant for a term certain is a tenant who occupies land under a lease agreement for a specific duration. The term can vary depending on the agreement, and the lease expires once the term ends.

Rights and Responsibilities:

- Rent Payment: The rent is generally specified in the lease agreement, and the tenant is expected to pay rent for the entire term.

- Occupancy Rights: The tenant has the right to occupy the land for the agreed term, after which the tenancy ends unless renewed. The tenant has no right to occupy the land beyond the term unless specifically agreed upon.

- Ejectment: The landlord has the right to evict the tenant once the lease term expires. However, if the tenant continues to occupy the land without objection from the landlord, the tenancy may be considered renewed or extended under the principles of implied continuation.

Conclusion:

The Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887 recognizes different classes of tenants, each with distinct rights and responsibilities. The occupancy tenant enjoys the most secure tenure, with hereditary rights and protection from arbitrary ejectment, while non-occupancy tenants and tenants at will have less security and are more vulnerable to eviction. Permanent tenants have a secure tenancy but without the right to pass it on to heirs, while tenants for a term certain have a temporary and fixed tenure with specific terms.

The rights of tenants, including rent payment, occupancy rights, and protection against ejectment, vary significantly across these classes, with greater protection granted to tenants with more permanent and secure tenancies. These distinctions play a crucial role in maintaining balance and fairness in land tenancy relations.

Question-Discuss the different classes of tenants under the Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887. How do the rights and responsibilities of each class differ in terms of rent payment, occupancy, and ejectment?

Law Relating to Rent under the Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887

The Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887 provides a comprehensive legal framework governing land tenancy relations in Punjab, especially with regard to rent, its fixation, payment, and the consequences of non-payment. The Act distinguishes between different types of tenants, each of whom may have varying rights and obligations in terms of rent. Below is a detailed examination of the provisions related to rent under the Act:

1. Fixation of Rent (Section 8)

Principles of Rent Fixation:

The Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887 provides a mechanism for fixing the rent of agricultural land. Rent can be determined by mutual agreement between the landlord and the tenant, but if no agreement exists or the existing rent is contested, the following principles apply:

- Fair Rent (Section 8): The Act allows for the fixation of fair rent for agricultural land, based on the prevailing agricultural conditions, the quality of land, and other relevant factors. The Fair Rent is fixed in such a way as to ensure that the tenant is not overburdened by excessive rent.

- Rent Agreement: In the case of occupancy tenants, the rent is often lower than that charged to non-occupancy tenants. If a tenant has been occupying the land for a long period, the rent may be fixed based on an established custom or usage in the locality.

- Rent in Cash or Kind: The rent may be payable either in cash or in kind (a portion of the agricultural produce). The rent in kind is usually agreed upon by the parties involved, and its proportion is determined by local custom and practice.

Procedure for Rent Fixation:

- Request for Rent Fixation (Section 8): A tenant may apply to a Revenue Officer for fixing the fair rent in case of disputes or where the rent is unreasonably high.

- Determination by the Revenue Officer: The Revenue Officer has the authority to fix fair rent after considering the relevant factors, including the fertility of the land, customary rents in the locality, and the economic capacity of the tenant.

2. Payment of Rent (Section 13)

Mode and Timing of Rent Payment:

- Time and Manner of Payment (Section 13): Rent is typically paid at the time of harvest or during the agreed-upon intervals, which may vary depending on the nature of the tenancy agreement.

- Payment in Cash or Produce: As noted earlier, rent may be paid in cash or in agricultural produce, depending on the agreement between the landlord and tenant. In some cases, landlords may agree to receive rent in the form of a share of the crop produced by the tenant.

Obligation of Tenant to Pay Rent:

The tenant is required to make rent payments in a timely manner, according to the terms of the tenancy. Failure to pay rent on time may lead to legal consequences.

3. Consequences of Non-Payment of Rent (Section 11, 14)

Non-Payment of Rent:

Non-payment of rent is a serious issue under the Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887. The Act stipulates various legal consequences for tenants who fail to pay rent as required under the tenancy agreement.

- Ejectment of Tenant (Section 11): If a tenant fails to pay rent for a certain period (usually 3 years for occupancy tenants), the landlord has the right to file for ejectment in the Revenue Court. Ejectment is a process through which the tenant can be legally removed from the land due to non-payment of rent.

- Arrears of Rent (Section 14): If rent is not paid on time, the landlord has the right to recover the arrears through legal action. A Revenue Officer can enforce the recovery of arrears of rent by attaching and selling the tenant’s movable property.

- Limitation for Recovery of Rent (Section 14): The recovery of arrears of rent is subject to a limitation period. If the landlord does not take action within 3 years, they lose the right to recover the arrears through legal means.

Further Consequences for Tenants:

- Penalty for Non-Payment (Section 11): In cases of repeated or continuous non-payment, a tenant may be liable to pay a penalty in addition to the arrears of rent.

- Right of Landlord to Increase Rent (Section 8): In some cases, if a tenant persistently fails to pay rent or violates the tenancy terms, the landlord may seek to increase the rent or impose stricter conditions.

4. Rent Recovery (Section 15)

Revenue Officer’s Role in Rent Recovery:

The Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887 empowers Revenue Officers to take action in the recovery of unpaid rent. This includes the right to:

- Attach the tenant’s property.

- Recover rent through sale of the tenant’s crops, movable property, or even land if necessary.

5. Rent for Land Held by a Tenant at Will (Section 9)

A tenant at will is one who occupies land without any formal lease agreement. The rent payable by such a tenant is usually based on an agreed-upon amount, but they do not have the right to continue occupying the land indefinitely.

- Rent Amount for Tenant at Will: The rent for such tenants is determined by the landlord and can vary at the discretion of the landlord. If the tenant fails to pay rent, the landlord has the right to terminate the tenancy immediately without notice.

6. Rent under Special Provisions for Non-Agricultural Land (Section 19)

For non-agricultural lands under tenancy, the Punjab Tenancy Act also provides special provisions for rent determination and payment, focusing on commercial lands and their specific usage.

Conclusion:

The Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887 establishes clear guidelines for the fixation, payment, and consequences of non-payment of rent. Rent is usually fixed through mutual agreement, but if disputes arise, the Revenue Officer can intervene to ensure that fair rent is paid. The Act imposes strict consequences for tenants who fail to pay rent, including the possibility of ejectment, recovery of arrears, and penalties. These provisions aim to balance the rights of landlords with the protection of tenants from arbitrary eviction or excessive rent.

Question:- Discuss the concept of ‘surplus area’ and permissible area under Haryana ceiling on Land Holding Act, 1972

The Haryana Ceiling on Land Holdings Act, 1972 was enacted to promote equitable distribution of agricultural land in Haryana by imposing limits on land ownership, preventing concentration of land in the hands of a few, and redistributing excess land to landless or marginal farmers. The concepts of permissible area and surplus area are central to this Act and are defined as follows:

Permissible Area

- Definition: The permissible area is the maximum extent of agricultural land that a person (including an individual, family, or other legal entity like a company or association) is legally entitled to hold under the Act. It is specified under Section 4 of the Act and varies based on the type and classification of land, such as irrigated or unirrigated land, and the irrigation intensity ratio.

- Determination:

- The permissible area is calculated based on the average yield and quality of the land. For example, the ceiling ranges from 4.046 hectares to 8.093 hectares (approximately 10 to 20 acres) depending on the land’s classification (e.g., irrigated by canal, tubewell, or unirrigated).

- For a family (including separate units like adult sons or their widows/children living with parents), the total land held by all members is aggregated to determine the permissible area.

- Landowners are required to select their permissible area through a declaration under Section 9, specifying the parcel(s) of land they wish to retain within the ceiling limit.

- Purpose: The concept ensures that individuals or families can retain a reasonable amount of land for personal use while preventing excessive landholding, thus promoting equitable distribution.

Surplus Area

- Definition: The surplus area is the portion of land held by a person that exceeds the permissible area. It is defined under Section 2(r) as “the area in excess of the permissible area.”

- Acquisition and Vesting:

- Under Section 12, the surplus area is deemed to be acquired by the State Government for public purposes, such as redistribution to landless farmers or other eligible persons. All rights, titles, and interests in the surplus area vest in the state, free from encumbrances, upon declaration.

- The government compensates landowners for the acquired surplus area, as outlined in the Act.

- Process:

- Landowners holding land beyond the permissible limit must submit a declaration under Section 9, detailing their landholdings and selecting their permissible area.

- The prescribed authority prepares a statement under Section 11, showing the total land held, the permissible area, and the surplus area. This statement is sent to the landowner and tenants for verification.

- If the landowner fails to comply or appear, an ex-parte decision may be taken to determine the surplus area.

- The landowner is directed to hand over possession of the surplus area within 10 days of the order, failing which action is taken under Section 13(2) to secure possession.

- Utilization: The surplus area is redistributed under the Haryana Utilisation of Surplus and Other Areas Scheme, 1976, prioritizing tenants in possession since before the appointed day (January 24, 1971), Scheduled Caste residents, and other landless persons.

Key Features and Provisions

- Ceiling on Land (Section 7): No person can hold land (as a landowner, tenant, or mortgagee) exceeding the permissible area after the appointed day (January 24, 1971). This applies to all agricultural land in Haryana, regardless of the capacity in which it is held.

- Transfers and Dispositions (Section 8): Transfers or dispositions of land after July 20, 1958, that exceed the permissible area under prior laws (e.g., Punjab or Pepsu laws) are disregarded when calculating surplus area, except in cases of inheritance or acquisition by the government or tenants. This prevents landowners from evading the ceiling through fraudulent transfers.

- Exemptions: Certain lands are exempt from the ceiling, including those owned by the government, universities, cooperative societies, or religious/charitable institutions. In 2011, Haryana amended the Act to exempt land used for non-agricultural purposes (e.g., industrial or urban development), benefiting real estate developers.

- Appeals: Any person aggrieved by an order under the Act can appeal to the competent authority.

Practical Implications

- Permissible Area: Allows landowners to retain productive land within the ceiling, ensuring they can sustain agricultural activities while complying with the law.

- Surplus Area: Facilitates land redistribution to address historical inequalities in land ownership, benefiting landless farmers and marginalized communities. However, implementation challenges, such as delays in surplus land acquisition and exemptions for non-agricultural use, have limited the Act’s effectiveness.

- Example Calculation: If a person holds 25 hectares of canal-irrigated land with a 45% irrigation intensity ratio and a 5 HP tubewell, the permissible area might include 2.5 hectares of ‘AA’ category land (tubewell-irrigated) and a portion of ‘C’ category land, with the remainder declared surplus (e.g., 9.3 to 17.48 hectares, depending on the selection).

Critical Perspective

While the Act aims to reduce land inequality, its impact has been diluted by exemptions, legal loopholes, and amendments favoring industrial and real estate interests. For instance, the 2011 amendment allowing unlimited ownership of non-agricultural land has been criticized for undermining the Act’s redistributive goals. Moreover, only a small percentage of surplus land has been effectively redistributed due to prolonged litigation and administrative inefficiencies, a trend observed across India’s land ceiling laws.

In conclusion, the concepts of permissible and surplus areas under the Haryana Ceiling on Land Holdings Act, 1972, are designed to balance landowners’ rights with the state’s goal of equitable land distribution. However, practical challenges and policy shifts toward industrialization have limited the Act’s transformative potential. For detailed provisions, refer to the Act on India Code or the Revenue and Disaster Management Department, Haryana.

Question- Describe the grounds of ejectment of a tenant under the Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887 by quoting the relevant provision of the Act in this Regard.

Under the Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887, the ejectment of a tenant refers to the legal removal of a tenant from the land held by him. The grounds and procedure for ejectment are clearly laid down in the Act, primarily in Sections 39 to 49.

📌 Key Provision: Section 39 of the Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887

Section 39 – Grounds of Ejectment of Tenant

“A tenant shall not be ejected from his tenancy unless:

(a) He has been ordered to be ejected under this Act, or

(b) He has ceased to be a tenant under the provisions of this Act.”

🔍 Grounds of Ejectment of a Tenant

- ### Non-payment of Rent (Section 44)

- If a tenant defaults in paying rent without sufficient cause, the landlord can apply for ejectment.

- However, if the tenant pays arrears of rent at or before the hearing, ejectment may not be granted.

- ### Breach of Conditions of Tenancy (Section 45)

- If the tenant violates any condition of the tenancy agreement (e.g., sub-letting, change of crop, illegal activities), he may be ejected.

- ### Damage to Land or Waste (Section 46)

- If the tenant causes damage to the land, buildings, or commits acts of waste, he is liable for ejectment.

- ### Unlawful Occupation (Section 47)

- A person occupying the land without legal tenancy (i.e., an unauthorized occupier) can be ejected under this section.

- ### No Right of Occupancy / Not Protected Tenant

- Tenants who do not have occupancy rights or are not statutorily protected may be ejected on reasonable notice or on the expiry of the lease.

📋 Procedure for Ejectment (Section 49)

- A landlord must file an application before the Revenue Officer or Assistant Collector.

- The tenant is given an opportunity to be heard.

- The officer conducts an inquiry, and if the grounds are proved, an order of ejectment is passed.

- If ejectment is ordered, it must be carried out following due procedure (no self-help or force).

⚖️ Protection to Occupancy Tenants (Section 5 & 6)

- Occupancy tenants enjoy strong protection and cannot be ejected easily unless they fall under the specific grounds above.

- These tenants often have hereditary or long-standing rights in the land.

✅ Conclusion

The Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887 safeguards the rights of tenants by not allowing arbitrary or forceful eviction. Ejectment must be based on statutory grounds, particularly under Sections 39 to 49, and follow due legal process. Occupancy tenants enjoy greater protection, while non-occupancy tenants may be removed for valid legal reasons like non-payment of rent or breach of contract.

QUESTION- Describe the Rights & Duties of tenants under Haryana Rent Control Act, 1973.

Under the Haryana Urban (Control of Rent and Eviction) Act, 1973, the Rights and Duties of Tenants are outlined to balance the interests of tenants and landlords. These provisions are mainly covered under Sections 4 to 11 of the Act.

🔹 I. RIGHTS OF TENANTS (As per relevant Sections of the Act)

1. Right to Pay Fair Rent – Section 4 & 5

- A tenant is entitled to occupy the premises at a fair rent, as determined by the Rent Controller.

- The landlord cannot charge rent beyond what has been fixed under the Act.

- The criteria for determining fair rent include:

- Cost of construction,

- Location and condition of the building,

- Taxes paid,

- Rent of similar accommodation in the same locality.

2. Right Against Arbitrary Eviction – Section 13

- A tenant cannot be evicted without valid grounds listed under the Act.

- Eviction requires an application to the Rent Controller and due legal process.

3. Right to Receive Receipt for Rent Paid – Section 8

- Tenants are entitled to receive a signed rent receipt when they pay rent.

- Helps in protecting tenants from false claims of non-payment.

4. Right to Sublet with Permission – Section 11

- A tenant may sublet the premises with the written consent of the landlord.

- Unauthorized subletting can be a ground for eviction.

5. Right to Habitability

- Tenants have the right to live in safe, hygienic, and habitable conditions.

- Landlords must ensure basic amenities like water, electricity, and sanitation.

🔸 II. DUTIES OF TENANTS (As per relevant Sections of the Act)

1. Payment of Rent – Section 6

- The tenant must regularly pay rent by the agreed date or as per the Rent Controller’s order.

- Non-payment can be a ground for ejectment under Section 13(2)(i).

2. Not to Cause Damage – Section 13(2)(ii)

- The tenant must not cause damage to the building or use it in a way that lowers its value or utility.

3. No Illegal or Immoral Use – Section 13(2)(iv)

- The premises must not be used for illegal or immoral purposes.

- Violation may lead to eviction proceedings.

4. No Unauthorized Construction or Alteration – Section 13(2)(iii)

- Tenants must not construct or alter the premises without written permission from the landlord.

- Doing so may result in eviction.

5. Not to Sublet Without Permission – Section 11

- Subletting without landlord’s consent is prohibited.

- Unauthorized subletting is a ground for eviction.

6. Restoration of Property

- On vacating, the tenant must return the premises in original condition, reasonable wear and tear excepted.

🧾 Important Case Law Reference (Optional for Study/Answer Writing)

- Hari Ram v. Ram Niwas, 1990 HR Rent Control Case:

Held that failure to pay rent as per Section 6 is a valid ground for eviction under Section 13.

✅ Conclusion

The Haryana Rent Control Act, 1973 provides balanced rights and duties to protect tenants from exploitation while ensuring that landlords’ interests are not jeopardized. Tenants must follow legal obligations, while enjoying security of tenure, protection against unfair rent, and proper living conditions.

Question- What do you mean by ‘rent’? Examine, the procedure for the enhancement and reduction of rent under Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887.

Definition of ‘Rent’ and Procedure for Its Enhancement and Reduction under the Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887 (With Case Laws)

📘 1. Definition of ‘Rent’ under Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887

The term ‘Rent’ is defined under Section 4(2) of the Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887 as:

“Rent means whatever is payable in money, kind or service by a tenant on account of the use or occupation of the land held by him.”

Thus, rent can be:

- Cash payment (money)

- Produce or kind (e.g., part of crop)

- Service or labor

It is the legal consideration paid by a tenant to the landlord for using the agricultural land.

🛠️ 2. Procedure for Enhancement of Rent

📜 Relevant Section: Section 31 to 33 of the Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887

✅ Grounds for Enhancement (Section 31):

A landlord can apply for enhancement of rent on the following grounds:

- Increase in productive power of the land.

- Increase in value of the produce.

- If the current rent is substantially below the prevailing rent for similar land in the area.

📝 Procedure:

- Application to Revenue Officer by the landlord.

- Notice to Tenant is issued for representation.

- The Revenue Officer may inquire, examine witnesses, and inspect land.

- A fair rent is fixed after considering:

- Soil quality

- Irrigation facilities

- Average produce

- Past rent paid

Section 32: Requires rent not to be enhanced during the currency of a fixed term lease unless agreed.

📉 3. Procedure for Reduction of Rent

📜 Relevant Section: Section 33

✅ Grounds for Reduction:

A tenant may apply for reduction if:

- There is a permanent decrease in the productive power of land due to:

- Flood

- Soil degradation

- Permanent failure of irrigation source

- Other natural calamities

📝 Procedure:

- Application made by tenant to Revenue Officer.

- Notice to landlord and inquiry by Revenue Officer.

- If justified, the rent is reduced accordingly.

🧾 Important Case Laws

1. Bansi Lal v. Ram Chander, AIR 1958 Punj 189

Held: Rent can be enhanced only if the conditions under Section 31 are strictly satisfied. Arbitrary increases not permitted.

2. Amar Singh v. Kartar Singh, 1963 PLR 210

Held: Enhancement or reduction should be based on actual productivity and market conditions, not mere intention.

3. Jowahir Singh v. Indar Singh, ILR (1915) Lah 276

Held: Tenant’s plea for reduction of rent must be based on permanent and not temporary causes.

⚖️ Principles Established by Law:

- Rent cannot be increased or decreased arbitrarily.

- All changes must go through the Revenue Officer with proper inquiry.

- Protection is provided to both landlord and tenant.

- The Act promotes fairness and prevents exploitation.

✅ Conclusion

The Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887 lays down a clear procedure for enhancement and reduction of rent through legal mechanisms, ensuring that both landlords and tenants are treated justly. The Revenue Officer acts as a quasi-judicial authority to adjudicate disputes based on land productivity, usage, and fairness.

Question- Define ‘Rent’. How it is recovered under the Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887?

Definition and Recovery of Rent under the Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887

📘 Definition of Rent (Section 4(2))

According to Section 4(2) of the Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887:

“Rent” means whatever is payable in money, kind or service by a tenant on account of the use or occupation of the land held by him.

📝 Forms of Rent:

- Money – Fixed amount paid in cash.

- Kind – A portion of the produce.

- Service – Labor or other services provided in lieu of payment.

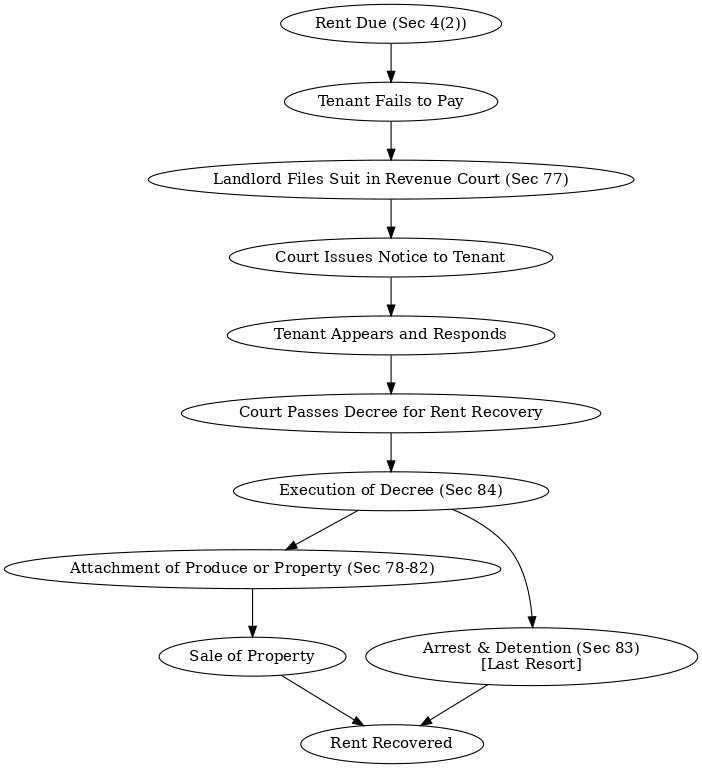

💰 Recovery of Rent (Sections 75 to 87)

📌 1. Voluntary Payment:

- Tenant is expected to pay rent on due date as agreed upon.

- If not paid, landlord can initiate legal steps.

📌 2. Recovery Through Revenue Court (Section 77):

- If rent is not paid, the landlord may file a suit in the Revenue Court.

- The suit must be filed within 3 years from the date rent becomes due.

📌 3. Distress and Attachment (Section 78-82):

- The Revenue Court may attach the produce or property of the tenant.

- This process is similar to civil recovery of debts.

- The sale proceeds are used to recover the outstanding rent.

📌 4. Arrest and Detention (Section 83):

- In extreme cases, warrants of arrest can be issued against the tenant if ordered by the Revenue Officer.

- However, this is rarely used and subject to judicial scrutiny.

📌 5. Execution of Decree (Section 84):

- Once the court passes a decree, it can be executed like any civil court decree:

- Attachment of land

- Sale of moveable property

- Imprisonment (as a last resort)

⚖️ Important Provisions Summary:

| Section | Content |

|---|---|

| Sec 4(2) | Definition of Rent |

| Sec 75-77 | Suit for recovery of arrears |

| Sec 78-82 | Procedure for distress and attachment |

| Sec 83 | Arrest and detention |

| Sec 84-87 | Execution of decree |

🧾 Conclusion:

Under the Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887, rent is a legal obligation of the tenant and can be recovered through courts if not paid voluntarily. The law provides for safeguards for both landlord and tenant by ensuring due process.

Here is a visual flowchart showing the process of rent recovery under the Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887:

📌 Click to view or download the flowchart

📚 Case Laws for Reference:

- Ganga Ram v. Mansa Ram (1917)

- Held that rent in kind must be converted to monetary equivalent when seeking recovery.

- Moti Ram v. Ram Ditta (1931 Lahore)

- Emphasized the necessity of timely suit filing within limitation period under Section 77.

- Balwant Singh v. Natha Singh (AIR 1952)

- Recognized the Revenue Officer’s power to attach property under rent recovery.

Question- Critically examine the object, scope and salient features of the Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887.

📘 I. OBJECT OF THE ACT

The Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887 was enacted during the British colonial period to regulate the relationship between landlords (zamindars) and tenants (occupiers) of agricultural land.

🎯 Key Objectives:

- Protect agricultural tenants from arbitrary eviction and exploitation.

- Define and regulate rights and liabilities of different classes of tenants.

- Provide a judicial mechanism for resolution of disputes.

- Establish rules for rent fixation, recovery, and ejectment.

- Encourage agricultural productivity through security of tenure.

Relevant Sections: Preamble, Sections 4 (Definitions), 5–7 (Classes of Tenants), 75–87 (Rent), 39–53 (Ejectment).

📜 II. SCOPE OF THE ACT

The Act applies to:

- All agricultural lands in Punjab and Haryana (including areas that were part of undivided Punjab pre-1947).

- It governs tenancy relationships involving rent-paying cultivators.

- It deals with occupancy rights, procedural safeguards, and ejectment laws for tenants.

Territorial Scope: Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh (as adopted), and UTs like Chandigarh where applicable.

⭐ III. SALIENT FEATURES OF THE ACT

1. 🔑 Definitions and Classification (Section 4 & 5–7)

- Defines important terms like tenant, landlord, rent, ejectment, etc.

- Distinguishes occupancy tenants (Section 5) and non-occupancy tenants (Section 6).

- Tenancy by custom (Section 7) recognized in certain regions.

2. 🧑🌾 Tenancy Rights and Security of Tenure

- Occupancy tenants have heritable and transferable rights unless barred.

- Tenants cannot be evicted without due process (Sections 39–53).

- Tenants acquiring long-term occupation may gain occupancy rights.

Case Law: Mst. Subhani v. Nawab, AIR 1941 Lah 222 – recognized customary tenancy rights.

3. 💰 Law Relating to Rent (Sections 75–87)

- Rent can be in money, kind or service.

- Revenue Courts are empowered to adjudicate rent-related disputes.

- Legal remedies for non-payment include attachment and sale of produce.

Key Section: Section 77 – suit for arrears of rent.

4. 🧾 Recovery and Ejectment (Sections 39–53)

- Landlord must apply to Revenue Officer for ejectment.

- Eviction only if tenant fails to pay rent, or breaches agreement.

- Protection against arbitrary eviction is central to the Act.

Important Case: Moti Ram v. Ram Ditta, 1931 Lah – emphasized due process in ejectment.

5. ⚖️ Revenue Courts and Officers (Chapter IX, Sections 88–95)

- Establishes Revenue Officers and Courts for disputes resolution.

- Special procedures and hierarchy of officers defined.

- Provides limited civil court jurisdiction in tenancy matters.

6. 📃 Appeals, Revision & Review (Sections 100–106)

- Multiple levels of appeal and revision provided.

- Prevents misuse of power and ensures fairness in decisions.

7. ⚖️ Customary Laws Recognized (Section 7)

- Local customs regarding land use, tenures, and community practices given legal standing.

🔍 CRITICAL ANALYSIS

✅ Strengths:

- Tenant-centric legislation ensuring protection.

- Judicial mechanism via Revenue Courts reduces cost and complexity.

- Recognition of customary law made it culturally adaptive.

- Regulated rent structure helped stabilize rural economy.

❌ Limitations:

- Landlords often exploited legal loopholes to eject tenants.

- Outdated in parts — fails to address modern landholding patterns.

- Doesn’t account for urbanization and non-agricultural tenancies.

- Revenue Courts often lack the judicial independence of civil courts.

📚 Conclusion

The Punjab Tenancy Act, 1887 was a progressive legislation for its time, aimed at balancing power between landlords and tenants. It brought in land reforms through legal recognition of tenant rights, regulated rent, and provided dispute resolution mechanisms. However, it needs periodic revision and modernization to reflect the changing socio-economic realities of rural India.